By: Nate Bek

Seattle's startup scene is growing, but it’s clear we have some work to do.

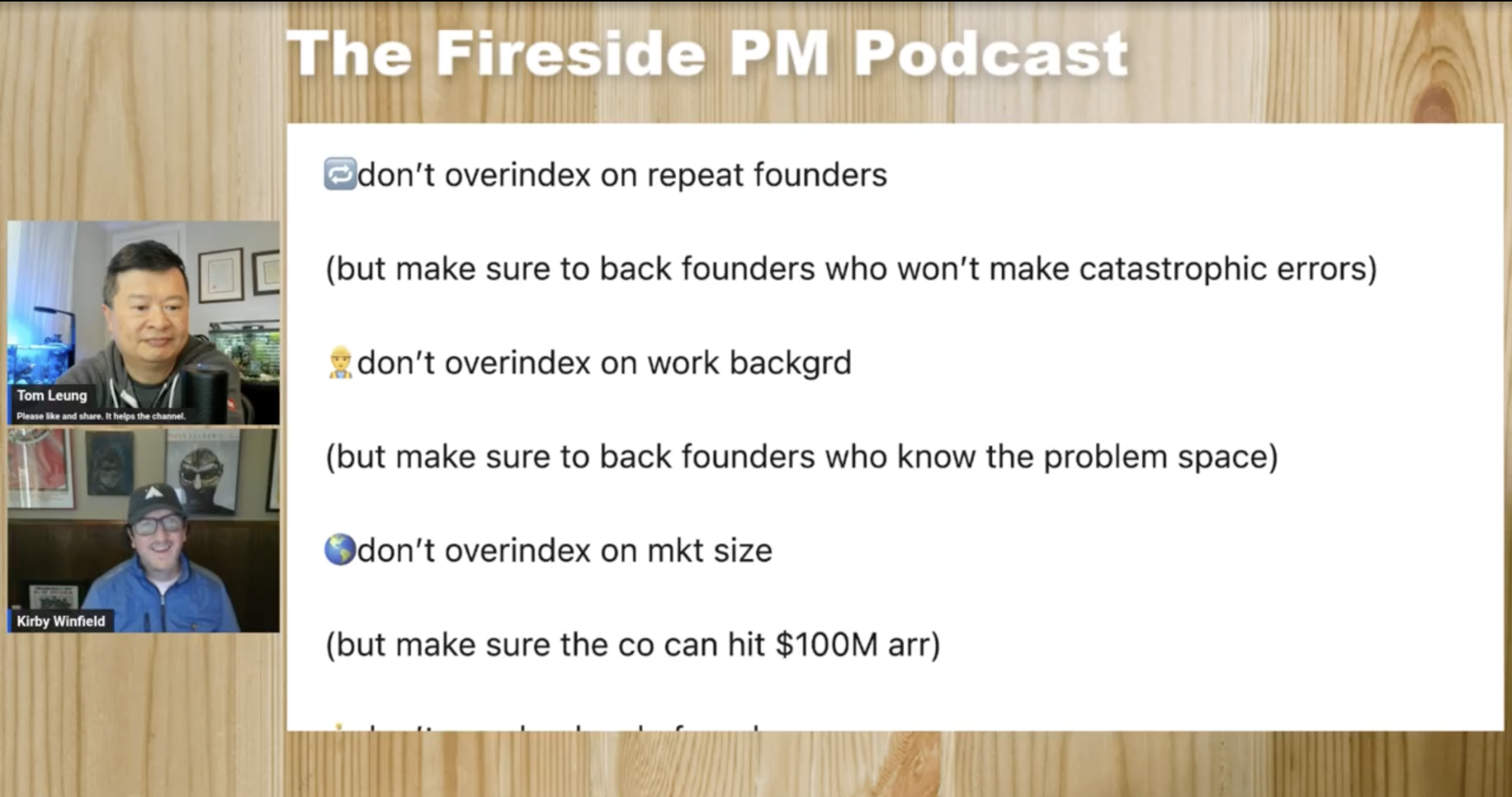

That was a main takeaway from our panel discussion last week featuring venture capitalists from top-tier firms including Brentt Baltimore of Greycroft, Victoria Treyger of Felicis, and Sunil Nagaraj of Ubiquity Ventures, moderated by Kirby Winfield. Their goal: analyze Seattle's startup landscape from an outsider’s perspective with active Seattle investments.

They see a city rich in technical talent but with several missing pieces. Go-to-market strategies often lag behind technical capabilities; capital is available, but frequently from outside the region; and stronger community cohesion is needed to bridge incumbent tech leaders with founder types.

Here are our five favorite quotes from the panel:

Go-to-Market Strategies:"Seattle founders, in general, are not as strong in go-to-market strategies or storytelling," said Victoria. Improving these areas are key for growth.

Practical Valuations: "In Seattle, you have more practical, down-to-earth people and more practical valuations," said Sunil. This approach leads to better outcomes.

Community Cohesion: "There seems to be this divide between the incumbent tech community and the non-incumbent, newer people," said Brentt. Bridging this gap can strengthen the ecosystem.

Founder modesty: “People are just nicer here,” said Sunil. “In the Bay Area, there's a sense of entitlement and puffing up, especially with incubators like Y Combinator cultivating a culture where being a jerk is almost expected. That doesn't happen in Seattle. Here, it's nice, nerdy people working together.”

Accelerators: Seattle needs a stronger accelerator layer, similar to Y Combinator, to help founders get early customers and build effective go-to-market plans, Victoria said.

Keep reading for the full transcript.

*We've edited this conversation for brevity. Enjoy! — Nate 👾

Kirby Winfield: I'm Kirby Winfield, founding general partner of Ascend. We focus on pre-seed investments, primarily with Seattle founders, and specialize in AI, data, vertical software, and the horizontal AI that supports these companies. I'm thrilled to have friends from California here today.

Brentt Baltimore: I'm Brentt Baltimore from Greycroft. Thanks for having me; I'm excited to be here. I've been with Greycroft for about eight years, starting in our New York office and then moving back to LA. Greycroft is a 19-year-old firm with offices in New York and Los Angeles, and we added a San Francisco office just under a year ago. I focus on data and applied AI. Our most recent investment in Seattle is Groundlight. Our oldest investment in Seattle is Icertis, which is now much later stage.

Kirby: A little known fact about Greycroft, Dana Settle, the founding partner, I went to high school with her. She’s a Seattle local and also a University of Washington alum.

Victoria Treyger: I'm at Felicis and have been with the firm for almost six years. We focus on seed and Series A, across all sectors. We specialize in B2B, AI infrastructure, and AI applications. I've also worked on financial software, like the office of CFO, fraud, identity, and health tech.

One unique aspect of Felicis is our global investment approach. We're based in the Bay Area, but some of our best companies, like Adyn (Netherlands), Shopify (Canada), and Canva (Australia), are from all over the world. It will be interesting to compare lessons from these ecosystems to Seattle's.

Our main Seattle investments are more recent, within the last two years. They include MotherDuck, a phenomenal company, and a cool AI infrastructure company called Predibase (co-founder Travis is based here). We also invested in Atlas Health and have a recent, yet-to-be-announced investment in Seattle.

Sunil Nagaraj: My name is Sunil Nagaraj, and I'm with Ubiquity Ventures. Ubiquity is my own small VC firm. I call it a nerdy and early venture capital firm because I love to code and focus on products and first pitches. I do about 1,000 pitches a year and have invested in about five companies here over the years.

While at Bessemer, I sourced Simply Measured and Auth-0. Under Ubiquity, I've invested in ThruWave, Esper, and Olis Robotics. I love Seattle and first got introduced to the city in 2003 when I interned at Microsoft as a PM. I fell in love with the city and visit as often as I can.

At Ubiquity, I focus on software beyond the screen. I use my current $75 million fund to write checks between $1 and $2 million for companies taking software off computers and putting it into the real, physical world. Some of my investments include software on cows, in space, in our ears, and in field devices. I tend to move quickly because I work alone. For example, with Auth-0 in 2014, it took just seven days from meeting the company to committing to their seed round, which grew into a $6 billion company in Seattle.

Kirby: So let's dive in. We'll start with a softball question to get everyone in a good mood, and then we might move on to more controversial topics. To kick off, what do you like about Seattle founders or teams? What unique qualities do you find in this ecosystem, given that you all invest in many different regions?

Brentt: What I love the most about Seattle is the amount of technical depth. Even years ago, when I first started building relationships with founders and folks operating some of the bigger companies here, I noticed this. Coming from LA and spending most of my time in data, the technical expertise here really stands out.

As a firm, we focus on go-to-market strategies and spend most of our time supporting our portfolio companies in that area. The strong technical foundation in Seattle creates a perfect marriage for us.

Victoria: I'll add one more point, which I think is both a positive and an opportunity. Seattle founders tend to be more humble than founders in some other areas.

Kirby: Does that lead to opportunities for investors coming in the market, like pricing? Is there more value to be had here? Sometimes maybe other markets, or is that not a consideration?

Victoria: In the end, venture is a business of outliers. You're trying to find the Auth-0s and MotherDucks, the massive exits. That's really what you're looking for. Whether you're paying a 15 post or 20 post for a seed, you pick the very best founders and companies. It doesn't matter.

Sunil: I agree with everything you said. I would add that Seattle has its own strengths. I'm an emotional person, and I work alone, so I really vibe with my founders. People are just nicer here. In the Bay Area, there's a sense of entitlement and puffing up, especially with incubators like Y Combinator cultivating a culture where being a jerk is almost expected. That doesn't happen in Seattle. Here, it's nice, nerdy people working together.

When I think about founders, they're super nice, down-to-earth, and genuine people. They're about getting stuff done, not about showing off or projecting an image. I love that folks here are more humble and down-to-earth.

I do think you get more reasonable valuations here. In Seattle, when you raise money, you leave more room in your valuation for bumps along the way. In the Bay Area, if you raise at a 25 pre and then 30 pre, there's not much room for error over the next 12 months. Any hiccup can lead to a down round, which is really annoying for many reasons.

In Seattle, you have more practical, down-to-earth people and more practical valuations. VCs still buy about the same percentage, around 20% at each round, but it's more like buying 20% of a $2 million round instead of a $5 million one. This leads to a more enjoyable process and can still result in outlier outcomes like we've talked about.

Kirby: Let's explore the cultural differences between founders, keeping in mind that we're generalizing. We know there are exceptions, but for discussion's sake, let's handle this topic generally. Some founders out here might be seen as more humble. This can be viewed positively or negatively. What are some positive and negative differences between a typical founder here and those in New York or the Bay Area?

Victoria: From my perspective, Seattle founders, in general, are not as strong in go-to-market strategies or storytelling, including engaging with the press. This is a generalization, so take it with a grain of salt. Our firm has invested significantly in Australia's ecosystem and seen incredible outcomes. I have three investments there, and my partner Wesley has two, including Canva.

Australia, to be honest, has one massive company, Atlassian, which has spun out all three of my investments. Seattle has Amazon and Microsoft. The biggest difference I've noticed is that Atlassian founders are very scrappy and GTM-focused from the start. By the time we led the seed rounds, they already had early revenue and customers without significant marketing spend. They know how to gain traction in a scrappy way, which I don't see as much with Seattle founders.

Kirby: Do you think there's something about founders who spin out of recently parabolic startups that have become great companies? When the growth amplitude within the last 10 years has surged from, say, $10 million to $1 billion, are those founders closer to the early journey? Are they more likely to have those scrappy, GTM-focused characteristics than someone coming out of Apple, Google, Amazon, or Microsoft?

Brentt: I see it a bit differently. There is no shortage of technical talent willing to take the risk of starting something new. However, there seems to be a shortage of go-to-market talent willing to take that same risk and leave bigger companies. We don't see as many CROs, COOs, heads of go-to-market, or GMs from rapidly scaling companies or large corporations like Microsoft or Amazon leaving their roles as quickly as technical talent. There's a gap in risk appetite.

Kirby: I think that's been the criticism for some time. While I might be a bit self-interested or close to it, I do see this changing as we create more successful outcomes. We now have more people who have been recently involved in growing companies. Ten years ago, it was almost impossible to hire a marketer in Seattle for a startup with fewer than five people—they just kept rotating through the same ten jobs. It's gotten better, but the criticism remains valid.

Sunil: There's a massive difference between going from zero to one versus being at a large company like Amazon or Google. At a large company, you have stability, insurance, a good salary, and, importantly, distribution. For example, when Microsoft launches a new product like Teams, they can leverage their existing customer base and automatically include it in an Office 365 subscription. This built-in distribution is a huge advantage for go-to-market efforts.

In my pre-seed deep tech investing, I think a lot about the spectrum between "look what I built" versus "look who cares." Building new deep tech innovations is challenging—you need advanced expertise and careful thought. However, communicating the value to customers is different. It's not about the technical specs but about how it benefits the user, like getting someone promoted at their job. This mindset shift is crucial.

If you come from a large company, you may not have exercised the zero-to-one distribution skills needed for startups, which are very different from scaling an established product. This reflects the talent gap, where only a few executives become the go-to experts for go-to-market strategies. This issue has been noticeable in my experience, where a handful of executives rotate as the "kingmakers" of go-to-market.

Kirby: What would it take for you guys to be pounding the table in Seattle 5-10 years from now?

Sunil: The real issues are capital and skills. These two are interconnected. Events like this can attract more people, which brings mixed feelings. More competition for us in Seattle deals, but overall, it's positive to have investors look beyond the Bay Area.

New York had a consumer vibe, but it's now more general. Seattle has strong technical and SaaS depth, which is very attractive. Most investors don't frequently visit Seattle events, even though it's an easy trip. Promoting more capital in the area is important. We have great firms in Seattle, and while more capital might bring competition, it's beneficial for the ecosystem overall.

Kirby: Nate recently did the research, and more than 90% of the venture capital in this market comes from outside Seattle. We always tell founders that while we hope they can raise funds from one of our few local series investors, these investors simply don't have the capacity to support all the founders. The numbers clearly show this.

You mentioned that most VCs don't think of this market. I always tell this story: when I was raising for my first CEO gig around 2009, I spoke to a big multi-stage investor who said, "Oh, you're from Seattle. They don't work that hard up there, do they?" Hopefully, this attitude has changed with some recent successful outcomes, but misconceptions still linger. Even recently, I've had conversations where people say they don't want to leave their current location because there's plenty of opportunities there.

What are some misconceptions that folks in California or other areas might have about this market, especially secondary markets like Seattle?

Sunil: You've already pointed out one major misconception: the number of large exits. For example, Seattle has had five exits over $10 billion, which isn't widely publicized. Another misconception is about the talent pool. Some people think, "You can start there, but eventually, you'll have to move because there won't be enough talent to scale." This is a myth as well.

If we can gather and promote data to counter these misconceptions, it would be huge. Addressing these two big objections—whether there are real exits in Seattle and if there's enough talent to scale—can significantly change perceptions about the market.

Victoria: One thing missing in Seattle is a stronger ecosystem like YC, which focuses on acceleration. Despite the criticisms of YC, they excel at helping founders get early customers, build GTM plans, and get off the ground. When I looked at some TechStars companies here, I didn't think they provided the same level of acceleration. Pioneer Square Labs feels more like an incubator.

That accelerator layer is missing here, which ties back to the go-to-market piece. Building such an accelerator would be exciting for Seattle's amazing entrepreneurs. Interestingly, there are now 160 YC founders in Seattle, all connected through a WhatsApp group. They help each other with early customers and distribution. This kind of community support is what Seattle lacks.

Brentt: I just want to add a little bit to that. I think the community element here is multifaceted. When I first started coming up here, I noticed two distinct groups: the old-school, incumbent community of founders, funders, and buyers, and a new community of folks. These groups didn't cross over much—they felt like two very distinct sets. At various dinners and events, you could sense the division when people from these different groups were at the same table. It felt strange.

Regarding capital, there's diversity in terms of stage. There are significant pre-seed and seed investors, including what you and your team are building, and other smart, value-add investors. However, the funnel thins out after that. In the acceleration stage, there doesn't seem to be the same volume of dollars willing to take risks. This funding tends to pick up at early B stages when companies are more proven, but there's not enough capital willing to invest in the critical acceleration phase. This results in either capital on the sidelines or not enough support for companies at that stage.

Kirby: I think it ties into something we wanted to discuss. When our companies hit that stage, almost all of them are raising in the Bay Area. The numbers show they have to, but it can be a challenge for founders based here who aren't working in the Bay, and who don't have investors like us on their cap table to connect them. We've done many investments, and probably 30 of them have been raised from the Bay Area because we have that network. But that isn’t available to everyone.

How would you recommend founders here, who maybe don't have that advantage, get in the flow? How can they get in the flow, whether it's participating in hackathons or having get-to-know-you coffees with investors before they need the relationship?

Victoria: My advice would be, and this is a new positive phenomenon I see in Seattle, to be very thoughtful when you raise your pre-seed and take your angel check. Bring investors into your cap table who are deeply connected outside of this area and have strong functional or industry expertise. I see this starting to change.

There are three amazing pre-seed funds that I know about, and there are others I might not know. For example, Kirby, who is very networked. Andrew Peterson, who has a pre-seed fund and is super networked in cybersecurity. If you're a security founder, you should take a check from him because he knows all the cyber investors outside of the Bay Area.

Another example is Tim Chen at Essence, who is a fantastic infra investor and one of the best I've met. Taking money from him is beneficial because all the top Bay Area and global firms follow what Tim is doing.

I don’t think get-to-know-you coffee chats are worth it, that’s just my take.

Kirby: You just saved everyone $1,000… What about founders actually embedding themselves and doing their business from places like San Francisco? From my perspective, we have a team that has been there for six months. They had been wandering the desert for a year, hacking and trying to find solutions. Being in the flow down there, they've figured out what AI infra problems actually matter. They've been able to network and talk to other builders and VCs. Now, I don’t have to worry about who’s going to do their next round because they’re there and connected. So, I’ve seen it work.

Sunil: I heard you mention a founding team that was initially struggling and then moved closer to their customers. This approach is spot on. The other details about being in the right place or meeting the right people don’t matter as much. What really matters is having happy customers. If you can bootstrap or find a cost-effective way to gain happy customers, that's the key to unlocking seed capital.

When you're looking for Series A, Series C, or beyond, having happy, paying, repeat customers will help you attract investors from anywhere, whether New York or elsewhere. It's more about proving customer interest quickly.

In a pitch, I’m most interested in hearing about your product and who it’s for. I want to know if people love it, keep coming back, or if your servers are overwhelmed by demand. That’s more important than how many times we've met for coffee or how often you stay in touch. Customer traction is what truly draws my interest.

While I do invest in some cases before customer traction, like with Esper, it’s usually in areas I know really well and can anticipate customer interest. In general, my advice is to focus on your customers above all else. Don’t worry too much about staying close to investors. Listen to your customers—they are the only ones who truly matter.

Audience Q&A: What's the biggest lever, in your opinion, that will get Seattle, not to become that amazing, complete ecosystem we all want, but that will take us on that path to being the amazing startup ecosystem?

Victoria: I'm going to go with acceleration, leadership, and more pre-seed funds. Pre-seed GPs, like Isaac sitting in the room over there, are really good at guiding founders through to the next round. This is a significant change in Seattle over the last five years. And, of course, there's Kirby.

The expansion of these pre-seed funds is crucial. Hopefully, they are raising money from companies like Microsoft and Amazon, which can be really helpful for distribution. That's how I see improving distribution in Seattle.

Brentt: I'm going to go in a slightly different direction and talk about the alignment of the community. What I mean by that is, everything we've talked about—capital, customers, and talent—is all here. Over time, at events, you'll see folks dwindle, but those who are truly committed will stay. That’s my honest take on the alignment part of it.

There seems to be this divide between the incumbent tech community and the non-incumbent, newer people. This isn’t unique to Seattle. For example, in Detroit around 2011 and 2012, there were the smart Ann Arbor people and the new, also smart, downtown Detroit people. Companies like Duo Security had to bridge that gap. Once the alignment happened, great things started to occur.